You always know it’s a good bug when your first reaction is, “How could this even happen?”

The other day, I was refining the dashboard of a web app we’re working on – as you do – and I noticed it was taking forever to load. Like, it had been loading in a single second, but now it was taking ten seconds. Something fishy was going on.

Naturally, I blamed React.

I mean, sure, in a modern web app there are many potential causes of a performance problem: third-party JavaScript, overburdened servers, bloated assets, missing database indexes – a list as long as your arm. But decades of building for the web told me that this was a frontend problem. I could just smell it. The page looked janky while loading. And despite being the least-bad approach for web frontends today, the React ecosystem is lousy with ways for a codebase to get tangled, slow, and fishy.

So to prove my theory, I explained to Claude1 that the dashboard was loading slowly, that it surely had some React problems, and to analyze it and rank them from most to least serious. And sure enough, Claude found a bunch of React fishiness – unnecessary re-renders, missing memoizations. We still weren’t on React Compiler, which I hadn’t realized. So I had Claude do a first pass on the easiest and most serious React issues, and…

It made almost no difference? Maybe it wasn’t React after all.

So, I rolled up my sleeves, and started investigating properly.

- Maybe the server really is slow? A little, but it’s not blocking the frontend.

- Was the problem in all browsers? No. It was somehow specific to Safari?

- Ah, it must be third-party JavaScript then. Intercom? No. PostHog? No.

- Okay, let’s really dig in to the performance timeline.

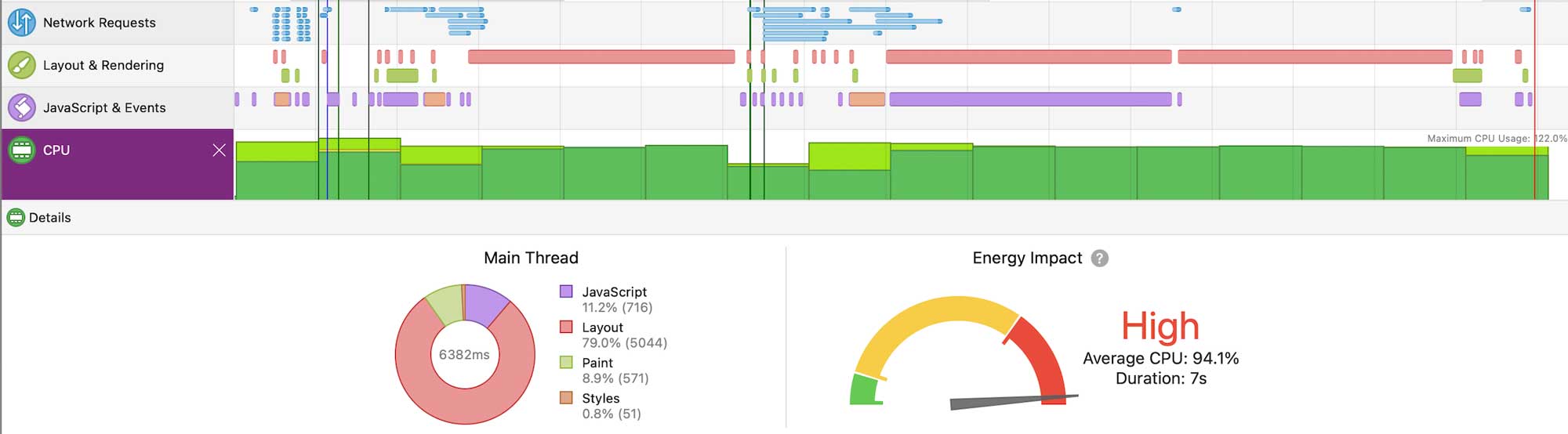

Now, the Safari performance inspector has diverged from the Chromium one over the years, and has gotten (on this page at least) rather flaky. But it painted a pretty clear picture: It wasn’t spending 7+ seconds parsing JavaScript, calculating styles, or loading from the network. It was using 94% of an M1 Max CPU on… Layout?

Digging into the details, it showed multiple Layout passes taking more than 1600ms each. For reference, that’s roughly 100x slower than it should be, so something was seriously wrong with how our page was being laid out. Flexbox can get a little slow, but not this slow.

Time to tear things apart

At that point, I reached for an age-old tool that has gotten more useful in the modern age: binary search. That is, you explain the symptom to your coding agent. Then you have it repeatedly remove stuff from your code that might be causing the problem, and see if that fixes it. When you find something that fixes it, you iteratively re-add everything until you have a minimal change that indicates the underlying issue, and thus a workaround.

This is especially fast if the agent can see the problem itself, but I didn’t have a command-line Safari perf analysis tool on hand. Still, after only 10 minutes of telling Claude whether a given change did or didn’t fix the issue, coaching it through how to think about what we’d just learned with each step, we’d found the culprit!

A heart emoji. ❤️

If we removed the emoji in our Send Feedback button (which I’d recently added), then Safari could lay the page out in 2 milliseconds. If we re-added it, the page took 1600ms for each layout, of which there were multiple.

Now, I like to use emoji in early prototype interfaces. They’re trivial to add, and load faster than images. Right? A single character of a font should not take 100x longer to render (or, according to Safari, “Layout”) than the rest of a dynamic React web app. Seems like I’d hit a Safari bug.

This is generally the “okay now I need a drink” moment in a Weird Bug Hunt. But it was still before noon, so I went to get another coffee instead.

When you find something that looks to be a bug in the browser, you want to submit that bug. To submit a bug, though, you can’t just attach your whole project. “Hey if you run this whole production app, Safari has a problem.” You’re meant to produce a minimal reproduction case: “Here’s a simple file that triggers the issue. Load it and see.” Even better, this means you’ll fully understand the problem, and can likely find a better workaround than “never use emoji in this app again”.

Making a minimal repro sample is a huge barrier for submitters, though, since fully boiling a full-fledged app containing proprietary stuff down to the minimal repro case is a ton of tedium.

Or, it used to be a ton of tedium! Related to their bug-isolating capabilities, coding agents are also particularly well-suited to producing minimal test cases. They can edit a lot of code at once, and it usually doesn’t take much creativity – you’re just iteratively removing as much as you can without making the bug stop triggering.

So, before long, I had a very simple repro case for the Safari team. And, in looking at the minimal repro code, it became very clear what the real culprit was. On my Mac, Safari 26.2 takes 1600ms to “Layout” the following HTML.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<link href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css2?family=Noto+Color+Emoji" rel="stylesheet">

<style>

body { font-family: "Noto Color Emoji"; }

</style>

</head>

<body>

💔

</body>

</html>

Curse you, Noto Color Emoji.

Fonts can have colors now!

Traditionally, fonts were just shapes. It would display in black, or white, or whatever color you chose. But in 2008, Apple shipped Apple Color Emoji in iPhone OS 2.2, and brought it to Mac OS X in 2011. Emoji’s rise in popularity led to demand for fonts that have intrinsic color.

Originally, Apple’s Color Emoji were basically a hack. They just stuck PNG images in a font, which was neither standardized nor resolution-independent. Outside a certain size range, they looked like butt. This led to four competing color font standards (from Apple, Mozilla, Google, and Microsoft) all being submitted to OpenType 1.7. According to Wikipedia, Microsoft and Apple added support for these different approaches, and that’s that.

But that – as it so often is – was not that.

You see, Noto Color Emoji is a Google font that is helpful in that it gives you consistent emoji rendering across platforms. We’d included it earlier to get decent emoji rendering on Linux (where we do some HTML-to-video rendering in the cloud, a technique that sounds horrifying but can be pretty useful). However, the font relies on COLRv1, a spec Google advises will make your apps load faster because it results in smaller emoji than bitmaps – and can fall back to supplying SVG for other browsers.2

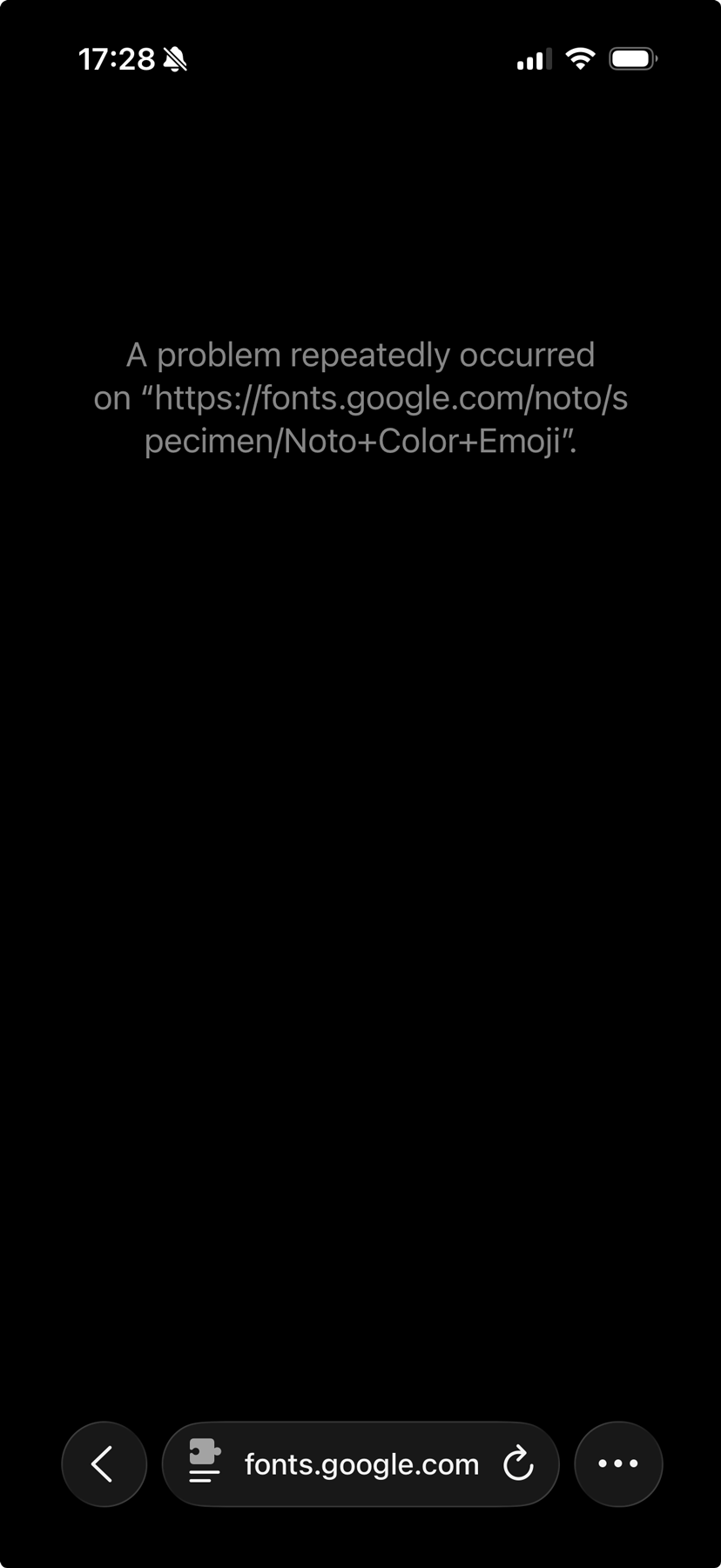

“Other browsers”, in this case, is Safari. And, I guess, “falling back to SVG” means spending 1600ms of “Layout” for a single character. If you’d like to see what this looks like scaled up, you can try loading the Google Fonts page that attempts to showcase all of the Noto Color Emoji glyphs on iPhone. (As of iOS 26.2, it goes poorly.)

After I mentioned the bug in a Slack, Daniel Jalkut filed it in the Safari bug tracker, and Simon Fraser on the webkit team has already commented, noting the slowness seems to be within CoreSVG. Chances are this will get fixed!

In the meantime, I’d like to contribute this humble finding to the search corpus: don’t use Noto Color Emoji on Apple platforms – list “Apple Color Emoji” first. At least, until the bug is fixed and the resulting Safari release is widespread.3

I’d also like to come clean on a little secret. As profoundly helpful as Claude was in debugging this – I surely fixed this problem 10x faster than I would have without it – I must admit, it was Claude that tipped us off to the existence of Noto Color Emoji in the first place. I suspect that, without the coding agent, we would have solved the Linux emoji problem in a more boring way (using an icon library) and not ended up with a weird slow emoji implementation.

It seems more true every month: these coding agents are very much like a power saw. Profoundly useful, and proportionately dangerous.

So, I suppose, here’s to Claude. The cause of – and solution to – all of startups’ problems.

-

As of publication, my default tool is Claude 4.5 Opus in Cursor or Claude Code. ↩

-

The COLRv1 spec is ostensibly for supporting a variety of new font techniques like gradients, palettes, nested glyphs, and the like, but so far it seems to be mostly used for emoji. ↩

-

Addendum, Feb 11: A couple folks from Google reached out informally about this bug. Dominik Röttsches noted that 🧺 is one of the hardest glyphs to render, but in my tests it doesn’t seem to trigger this bug at all – ❤️ and 🤯 take 1600ms to lay out, but 🧺 and 🫠 take 0.2ms, implying it’s a glyph-specific problem.

This meshes with Tom Roggero’s note that the font can be patched to improve performance. I’ll post another update if I hear that the font has been patched, which would surely be faster than a new version of Safari needing to propagate! ↩