Recently my team has been putting together some case studies. You know, telling the story of things we’ve built in a more timeless way than a 6-year-old blog post exclaiming “this is launching today, check it out!” with a link that has since become a 404.

When it came time to revisit the development of Two Spies, most of the tiny stories that went in to such an fun project didn’t make it into a one-page case study. So, I wanted to share one of those many details: how the game’s city-closing logic came about.

It all goes back to our extensive play testing.

CUE: That one harp sound effect that for some reason means a flashback is happening.

We had a problem – one common in many games’ evolution. Some rounds would be a lot of fun, and some rounds would be damn boring. In particular, depending on what your opponent did, rounds could drag on and on.

We made a number of iterations to improve how fast rounds completed. We wanted to offer more player abilities that kept things moving, present more interesting decisions, and make sure you could always overcome a player that was “turtling” – you know, hiding in a corner all game with their head in their shell.

Before long, we’d achieved our goal: hiding in a corner doing nothing was an objectively bad strategy. Unfortunately, however, despite the strategy being bad, players would still sometimes try it. You know, to be annoying. And when they did, the round would last forever. Well, not forever, but maybe 4x as long as normal. Which is 16x as long as you want a game to last, if your opponent is just sitting on their ass somewhere, hoping you’ll make a mistake before you overpower them.

Back in the day, game designers would cap round length with some kind of time limit. It worked, but it always felt a little unsatisfying. Luckily for us, Fortnite and PUBG had recently made famous a much better anti-turtling mechanic: The Storm. The idea being that as the game progresses, the area you can play in shrinks, pushing y’all together into an exciting endgame showdown.

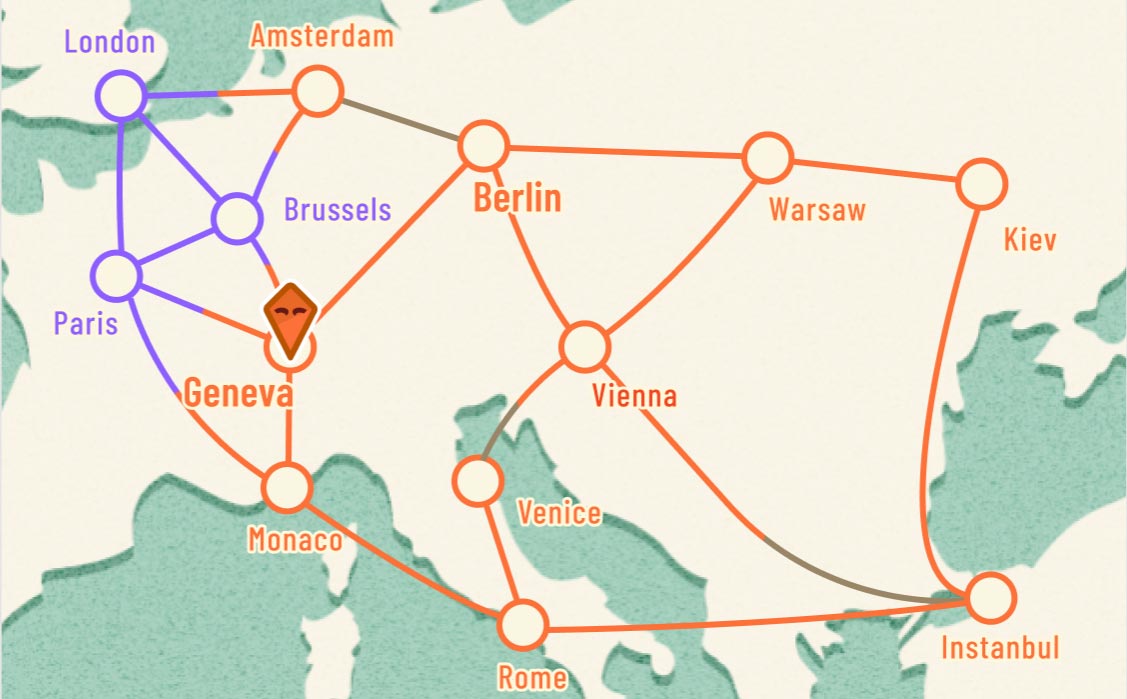

So I quickly hacked together a prototype that would close cities at the edges of the map if the game went on too long – and it worked! Usually. Usually it worked. Occasionally, it would close a city that connected one half of the map to the other half.

This was… not great. If the players were on different sides of the map, it would turn an overlong game to an interminable one. Curses.

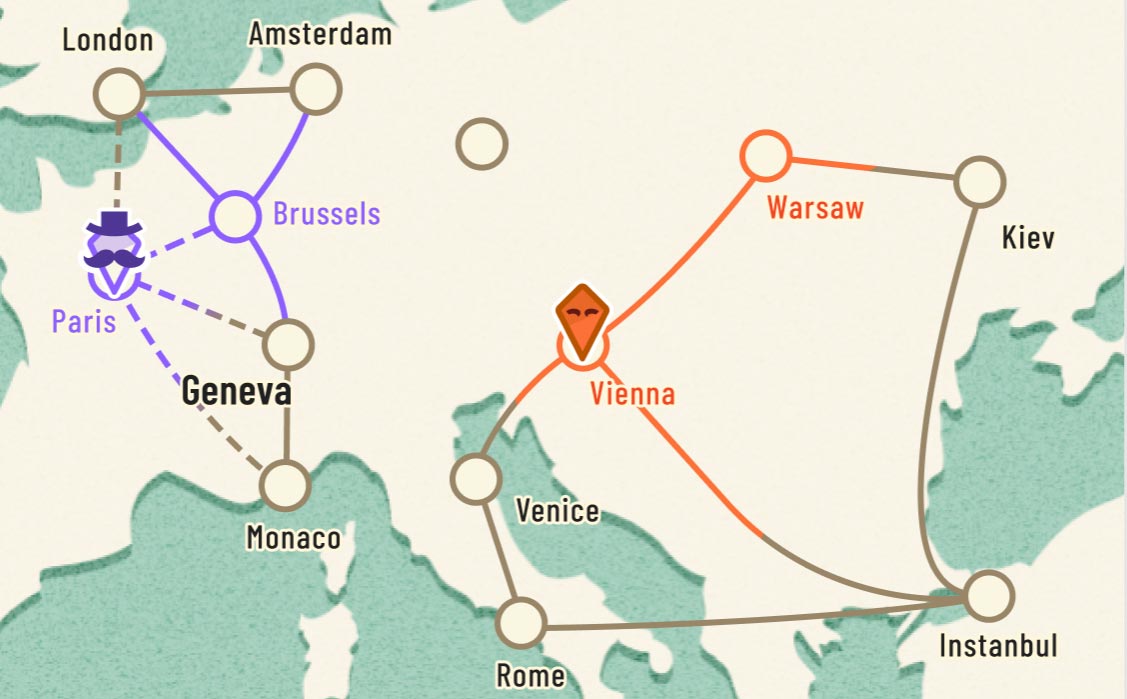

So what I needed to do was exclude a city from closing if it would divide the map. Using math.

As it happens, a Two Spies map is what they call, in math-land, a graph. A bunch of connected nodes. So you can google “graph theory identify node that splits graph” and learn that such a node is called an “articulation point”. Of course I didn’t need to Google this, because I totally remembered all sorts of graph theory details from university. But FYI there are a lot of resources for this stuff online.

So cool, I find an open source example of finding articulation points, port it to Swift, and before long the game will no longer split the map. Success!

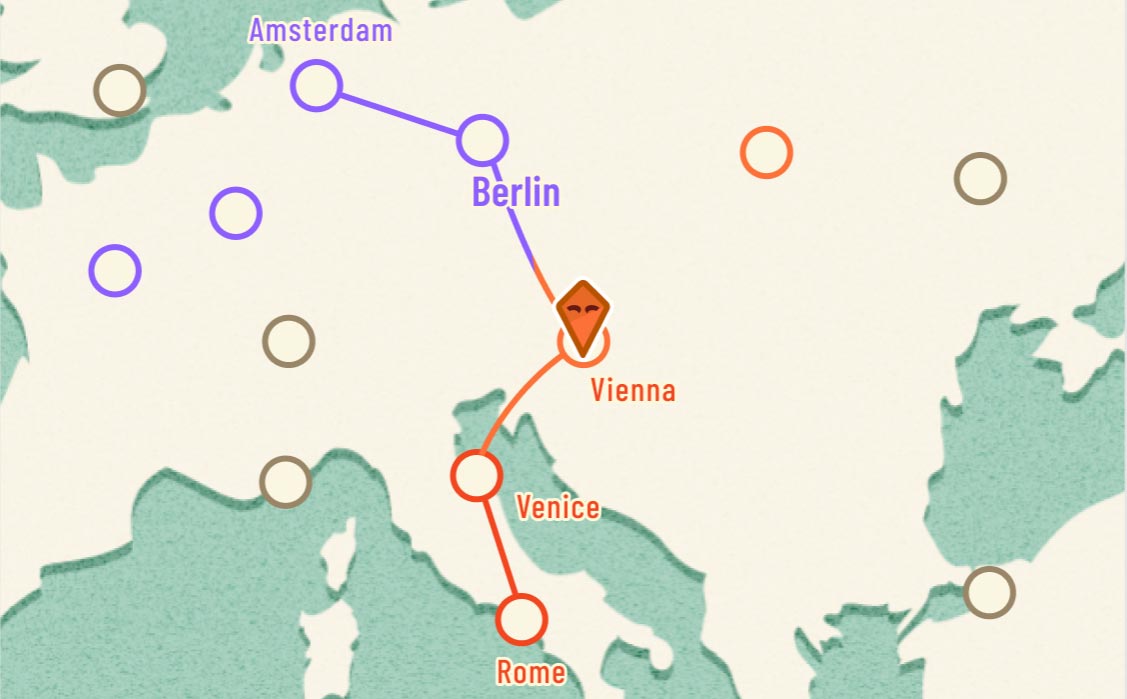

Except there was one remaining problem. Closing cities semi-randomly would sometimes leave a string of cities connected in a one-dimensional line. Now, there are some games that are interesting to play in one dimension – QWOP, for example – but Two Spies was not one of them.

So, goal #2 was: don’t create long lines of cities. Unfortunately, unlike the search term “graph theory identify node that splits graph”, there aren’t a lot of useful results for “graph theory identify node that doesn’t make graph more… liney”1. The solution here used an inelegant but effective search through the possible choices, weighing them for this factor and a few others that would tend towards maintaining an interesting map shape as it shrank.

Was it easily explainable to players? No. Was it mathematically pure? Very no. But in the end, it was fun. And players stopped asking how the game closed cities since it stopped feeling frustrating or weird, and seemed “natural”. Once these changes rolled out, they went back to commenting on more interesting things, like how to strategically taunt their opponents.

Building great products often looks like this. A series of tiny improvements, built out of equal parts observation, experimentation, and re-evaluation. And occasionally, a little bit of math.

-

Addendum, Feb 2026: Luke Salamone, an ML engineer at TikTok, recently solved the “Two Spies city closing problem” using math. Turns out, the answer to “how do you remove a node from a graph without making it more ‘liney’” is to do long-term minimization of the graph’s Weiner number using beam search! ↩