The first big wave of Apple Intelligence features are arriving shortly, with iOS 18.2. For the last month, a beta has been available, offering a peek into this new AI-powered future. I’ve been curious what Apple’s ML teams have been cooking, especially given the industry-leading security and privacy commitments they’ve made, so I checked them out.

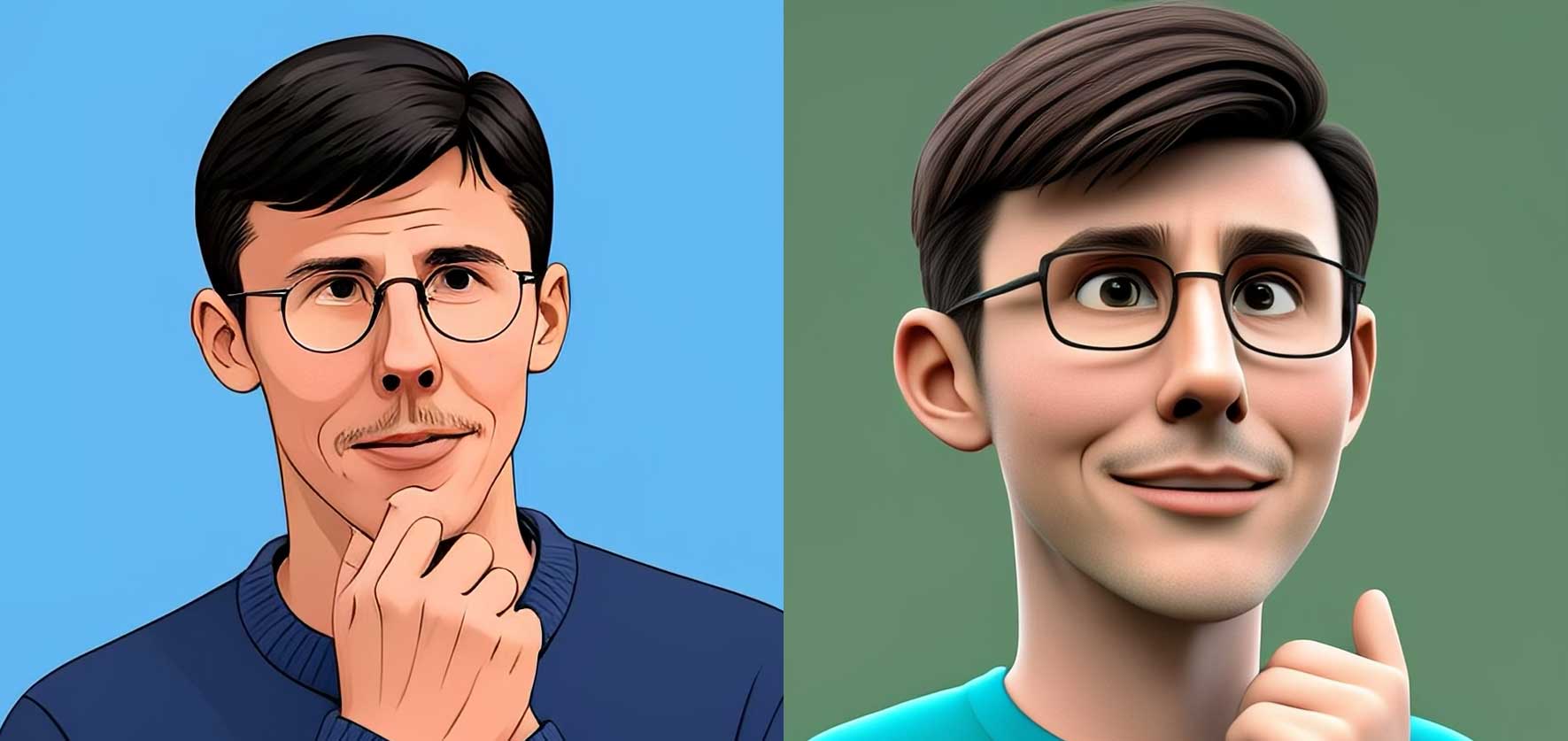

For example, the new Image Playground offered to generate an illustration of me, so I put it to task. I gave it a reference photo, and tapped one of the suggested backgrounds: “forest.”

My reaction to this was, “Hmm. 🤔”

My reaction to this was, “Hmm. 🤔”

Instead of just using an emoji, like it’s 2023, I wanted to generate an image of myself with a “hmm” expression. So I tried some prompts like “hmm”, “hand on chin thinking”, and the 🤔 emoji itself. I tried both the “illustration” and “animation” styles. Eventually I did get images that evoked “hmm” – though not how I originally imagined.

Hmm.

Hmm.Concerned that I had a cursed face, I asked if I was the only one so afflicted. Myke Hurley sent me the following, in solidarity.

Not sure what prompt Myke used for this photo – perhaps “hung over, forlornly contemplating one’s cursed face”.

Not sure what prompt Myke used for this photo – perhaps “hung over, forlornly contemplating one’s cursed face”.So what is going on here? Why are these new whiz-bang AI features creating underwhelming results? Why does my hand have seven fingers?

The answer, is strategy.

The Magic of On-Device Models

Apple’s strategy for generative AI Apple Intelligence is to run inference, as much as possible, locally on-device. This makes a lot of sense for Apple: it takes advantage of their excellent Apple Silicon hardware, it bolsters their promise of privacy as a core value, and it avoids needing to pay the server costs for a billion users’ push notification summaries – or sad AI portraits.

To make this possible, they’ve trained some models that are small enough to fit on an iPhone. Apple platforms now ship with a ~3B-parameter language model, paired with a number of little adapters they can swap in at runtime to tune it for tasks like summarizing notifications, proofreading text, or making prose friendlier. They’ve also included an image generation model, with adapters to render in the style of emoji, Pixar-like “animation”, and the dreadful “illustration” aesthetic showcased above. They also have a Mac-specific local model, which can power improved autocomplete when writing Swift in Xcode.

In some cases, this on-device approach is effective. I love it when 18 messages in our neighbours’ WhatsApp are summarized as, “Smoke detector issue resolved; ripe avocado requested.” Joanna Stern loves getting summaries like “Garage door opened and closed repeatedly; now closed.”

Yes, the summaries are imperfect – as you’d expect from a small local model. It sometimes makes statistically-likely but incorrect assumptions, like claiming that famed boxer Mike Tyson won his fight, or telling Joanna that her wife has a husband. While state-of-the-art models like GPT-4o or Claude 3.5 Sonnet make mistakes like this less and less frequently, the local iOS model is roughly 1% the size of those frontier models.

Still, it feels like on-device is the right tradeoff for notification summaries. The work of constantly summarizing and re-summarizing a billion push notifications daily is best left to the devices receiving them, and the fact this 1.0 version of the feature is already partially useful is a good sign in this regard. Now comes the iterative work of improving the training data to better understand the cases it’s struggling with – from sporting events to spousal genders.

Another feature that seems suitable for on-device processing is Proofread. Personally, I find the iOS 18.2 UI objectionable – you need to remember to trigger it, at which point it analyzes your document, then applies two dozen improvements all at once, forcing you to then review and undo many of them. But it really does find some typos and errors. The natural evolution of this feature is to become a more-advanced form of spellcheck, passively underlining phrases and typos with suggested improvements. The current UI may be clunky, but the AI part works well.

With other features, things are rougher.

While an underpowered-but-automatic notification summary can be better than nothing, there isn’t a lot of purpose to an underpowered image generation app. You can tell from the name that Apple knows “Image Playground” is, at best, a toy. But most of the fun of playing with image generation comes when you get an impressive result. Anybody who has seen outputs from state-of-the-art image generation tools like Midjourney, Flux, or Leonardo.ai will find Image Playground disappointing.

It sometimes generated me with crossed eyes, but never when I asked for it to.

It sometimes generated me with crossed eyes, but never when I asked for it to.At least you can have some fun trying to get it to generate things it doesn’t want to. The safety screws are very tight on this one, but I was able to get a duck butt by prompting “image of a duck looking away from behind.” When it does something funny, though, it’s usually by accident.

Luckily, Apple has a plan for how to handle generative AI tasks that are too difficult for local inference.

To the Cloud!

For work that requires a larger model, Apple has Private Cloud Compute. They’ve smartly leaned hard into their culture as a privacy-first company, and developed a way to do GenAI work on the server in a remarkably private and secure way. Like the on-device strategy, this approach makes a ton of sense for Apple, since it leverages their existing strengths in business model, secure toolchains, and Apple Silicon.

While easy tasks are handled by their on-device models, Apple’s cloud is used for what I’d call moderate-difficulty work: summarizing long emails, generating patches for Photos’ Clean Up feature, or refining prose in response to a prompt in Writing Tools. In my testing, Clean Up works quite well, while the other server-driven features are what you’d expect from a medium-sized model: nothing impressive.

Users shouldn’t need to care whether a task is completed locally or not, so each feature just quietly uses the backend that Apple feels is appropriate. The relative performance of these two systems over time will probably lead to some features being moved from cloud to device, or vice versa.

If you’re curious, though, you can deduce which features use Private Cloud Compute, because they don’t work offline. In my testing, it seems like most current features do not go to the cloud. I was surprised by this at first, but Ben Thompson recently pointed out that Apple does not seem to be investing in massive cloud AI capacity. It seems they feel their current course is going to be enough.

Speaking of the current course, we also have Siri. Siri also runs mostly on the cloud, but rather than being a whiz-bang novel generative AI technology running on Apple Silicon, it’s an incremental evolution of 15-year-old tech with a sparkly new animation slapped on it.

The animation is nice.

But like Alexa and Google Assistant, Siri will need to be totally rebuilt to fully take advantage of transformers and modern LLMs. Anybody who has tried ChatGPT Advanced Voice Mode since it was released in September knows that previous-generation voice assistants are now deprecated technology. Inconveniently, though, it takes more than 3 months to turn an amazing but inconsistent and expensive demo into something that can replace a load-bearing daily tool like Siri for a billion users.

Google has chosen to hack around this problem by splitting their voice assistant in two: you can talk to Gemini Live, which behaves more like a frontier AI assistant, or you can talk to old-school Google Assistant, which is dumber but can turn on and off the lights. This is a janky tradeoff, but it gets the new stuff in folks’ hands faster while they retool everything.

Apple, of course, does not want to put janky stuff in folks’ hands. They want to offer a seamless voice assistant for everybody, something that can both meet our suddenly raised expectations of how we converse with technology, yet also reliably do basic things like set timers and turn the lights on and off. Given the scale and cost of serving an assistant like this, Siri still needs to be able to serve basic requests locally on-device. This is a hard problem. It’s a lot less fun to be on the Siri team, saddled with a decade of user expectations, than on the ChatGPT or Claude voice teams right now.

While Apple works on whatever this next-generation thing will be, Siri has flipped from a sorta-unreliable tool we joke about but sometimes use and appreciate, to being embarrassingly behind the curve of technology. iOS 18.2 makes the old Siri a bit more flexible with phrasing, probably by stapling a little transformer model into some part of the legacy architecture, but it’s still obviously old Siri.

In the meantime, if you want to talk to a frontier LLM, you need to source it elsewhere.

There’s an App for That

The final leg in Apple’s GenAI strategy stool is for state-of-the-art model providers to offer their products on Apple’s platforms. Famously, iOS 18.2 will let ChatGPT (and, theoretically, other assistants) integrate into Siri for handoff when Apple’s assistant recognizes that a question is out of its league.

That’s kind of neat. But in order for the feature to be useful, Siri needs to be good enough that you reach first for Siri, and then wait for the fallback procedure when it bails. If it does bail, it passes to a second-rate version of ChatGPT, which doesn’t have its advanced capabilities like web search and data analysis. And even then, Siri sometimes still falls back instead to good old, “Here are some results I found on the web for seriously why is this so bad it’s 2024 for god’s sake.”

Savvy users, increasingly, are reaching directly for ChatGPT or Claude when they need assistance. While some features – like notification summarization – can only be offered by the OS, tasks that you undertake explicitly – like getting help with something – generally get better results from a frontier model. Luckily, all Apple Intelligence-enabled iPhones have an action button, which is easily mapped to a more advanced assistant. On Mac, you can map the excellent ChatGPT Mac app (or the horrendous Claude Mac app) to ⌥-Space.

On the Mac in particular, these frontier models are getting more useful and featureful at a breakneck pace. Anthropic introduced a preview of “computer use” a month ago, which lets Claude use a computer to do tasks like use websites, enter data, and run terminal commands. OpenAI added a “work with” feature a couple weeks back, where ChatGPT can directly read from and write to Mac apps like Xcode and Terminal.

Meanwhile, AI coding startups like Cursor and Windsurf are going way beyond what can be done in Xcode, further tilting the scales in terms of how easy it is to build certain kinds of web apps, when compared to building in Xcode. Apple knows this is a problem, and has announced an upcoming “Swift Assist” feature will be coming to Xcode at some point. Still, with the pace of improvements coming out of these dev tool startups, Apple is going to be hard-pressed to keep pace on their traditional yearly update cycle.

Which brings us back to strategy. For many years, Apple has kept an annual release schedule, releasing the vast majority of new operating system features in step with their yearly iPhone hardware. With Apple Intelligence, they’ve switched instead to rolling out improvements throughout the year. While it’s fun to joke about Apple marketing features that haven’t been released yet, this more rolling, incremental release strategy is a savvy response to the intensity of the moment.

So at a strategic level, Apple Intelligence seems to be on a rational track. For folks used to making use of cutting-edge GenAI features, though, the updates so far are a little underwhelming.

Apple Intelligence: it’s good for Apple, and okay for you.