In the olden days, video calls were hard.

Circa 2012, if your next meeting was online, it was important to start the process 5-10 minutes early. The process, at that time, was some or all of the following incantations and rituals:

- Find the meeting URL

- Find the meeting passcode

- Download a specific videoconferencing app

- Agree to and accept various things

- Dial in separately to get audio

- Troubleshoot your audio or video

- Wait for an update to download

- Wait for the videoconferencing app to restart

- Wait for your whole computer to restart

- Repeat some of the above steps, now that your computer has restarted

With luck, you would eventually be in the meeting. The other participants, often, would not be. Regrettably, each participant also needed to do the incantations, and they might not have started early. They might even be stuck.

For example, the person you’re meeting might think they’re waiting for you, so they’ve multi-tasked to another app – but surprise! GoToMeeting or WebEx or whatever actually needed them to click “OK” or “Update” or “Ẓ̴͝a̴̡̕l̷̙̓g̶̫̔ó̸̻” to continue the joining process. After 5-10 minutes you would politely email your colleague, asking if they were still joining. Often enough you’d find yourself attempting to help people troubleshoot the above steps via email, which was… not enjoyable.

This was all obviously bad. Any user could see it was bad, but it seemed – oddly – like the companies supporting these apps were kind of blind to it. Or, at least, their enterprise customers weren’t demanding better.

As the story goes, Eric Yuan, then an executive at WebEx, was aware how clunky these product experiences were, and was ashamed of it. He felt that customers deserved a more user-centric video product, with excellent call quality, that ensured anybody could join a call with one click.

In January 2013, his new startup launched Zoom 1.0. They employed some clever tricks to make sure Zoom seamlessly installed and stayed up to date, so anybody could always join a call in one click. They pushed hard to ramp up the video quality. They prioritized UX at all costs.

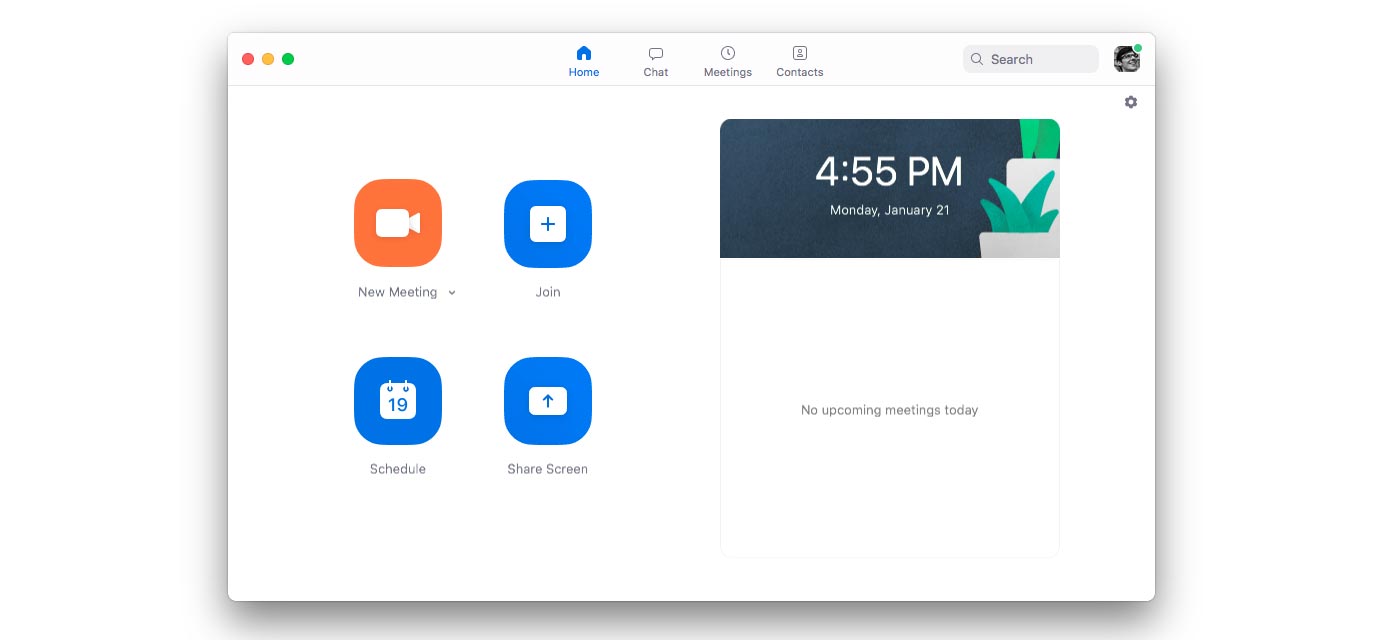

Zoom as it once was.

Zoom as it once was.

The formula worked. A few months after launching 1.0, Zoom had 1 million users. In April 2019, they IPOed with $600M of revenue, were profitable, and were doubling yearly. By then they were well-known as the video app with the best call quality and UX, so when the pandemic happened the following year, Zoom was propelled to household name status.

Today, they have over $1B/yr in profit, and continue to grow. Zoom is one of the great startup success stories.

It’s also slowly falling apart.

Enterprise rot

Success at scale always causes problems. Enterprise software success, doubly so.

The first hurdle for Zoom, shortly after their IPO, was security issues. These ranged from underpowered encryption to leaky analytics to the revelation that their legendary one-click meeting flow was itself a security vulnerability. With market dominance in hand and billions of dollars of enterprise revenue on the line, Zoom started to unwind their approach of usability at all costs. Zoom founder Eric Yuan on this shift:

One-click is important. However, you need to make sure there’s not any potential issue, any potential violation of the operating system. Sometimes we have to sacrifice usability for privacy or security, that’s exactly what we did. We now think security or privacy [is] even more important than that.

And objectively, this is good! We want the software everybody uses to communicate to be private and secure. But it’s also a change in mindset from what made the product great in the first place. The defaults get locked down, the settings panels balloon, and Zoom is that much less likely to incubate the next team communications breakthrough.

Zoom was also one of the companies most thrashed around by the pandemic. While from the outside the surge in usage might have seemed like a blessing, it ultimately caused Zoom more trouble than it was worth. Yuan again:

I really wish there was no COVID. Zoom would be a much better company today. COVID, I do not think really helped us that much except for the brand recognition. For everything else, I feel like there was a negative impact to our business in terms of culture, and growth, and the internal challenge, or the competitive landscape. Everything else… I feel like it’s not good for us.

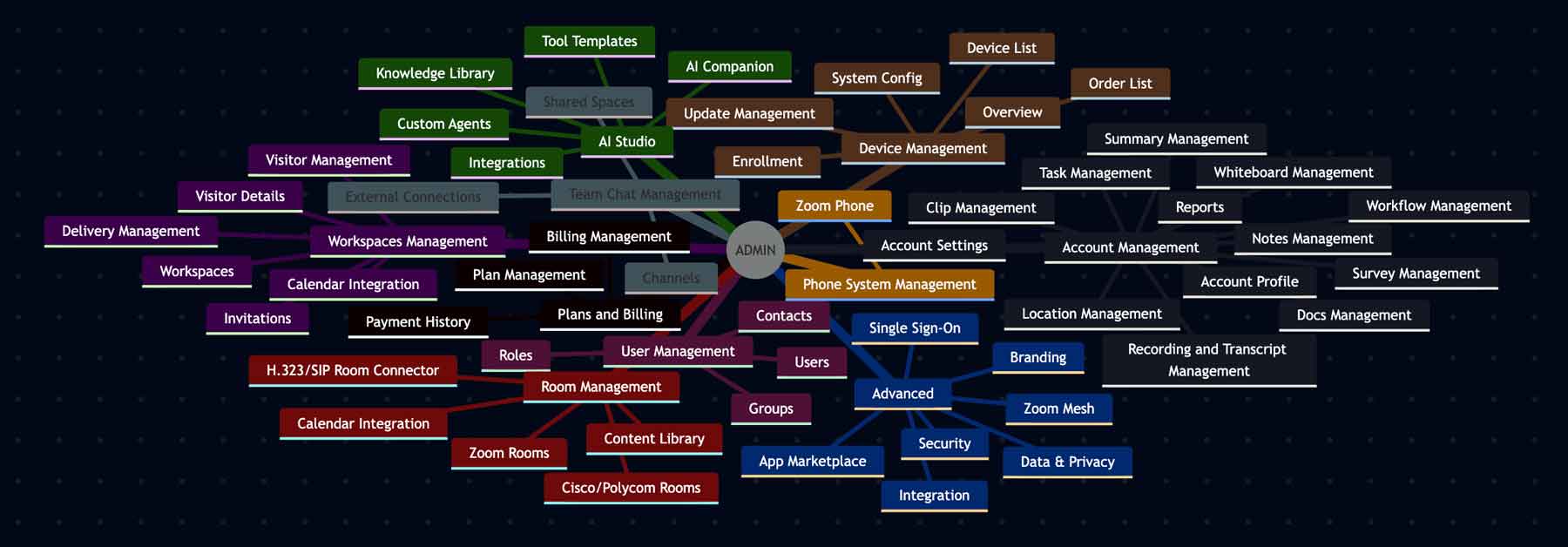

When your company goes from 2000 employees to 6000 in 2 years because of an event outside your control, you’re gonna have a bad time! You’re also going to get even more settings screens. How many settings, you ask?

The first two layers of Zoom’s admin settings now offer 63 sections and sub-sections worth of settings. These sub-sections are further divided into as many as 17 sub-sub-sections, which are then divided into as many as 12 sub-sub-sub-sections.

The first two layers of Zoom’s admin settings now offer 63 sections and sub-sections worth of settings. These sub-sections are further divided into as many as 17 sub-sub-sections, which are then divided into as many as 12 sub-sub-sub-sections.

Developing a clear and coherent product is hard. Developing a clear and coherent product with 6000 other people is even harder!

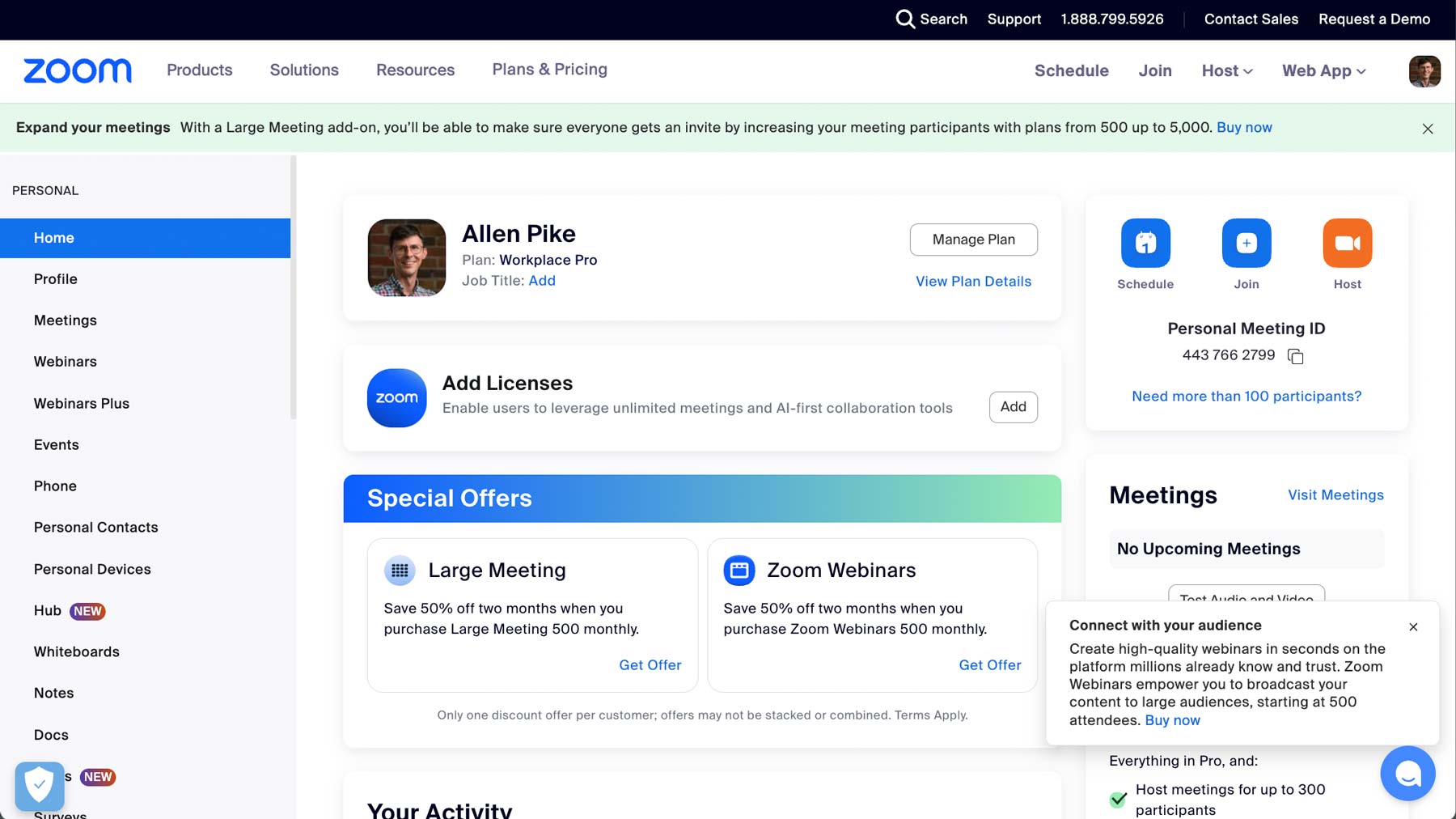

The other day I had to log in to Zoom to change one of these myriad settings. Shown below is what Zoom looks like today when somebody at a 2-person startup logs in.

Now. In your opinion, what is the ideal number of times this screen should try to sell a startup an upgrade to allow over 100 people in a meeting? Maybe… 6 separate upsells? (The sixth is hard to spot, it’s partially hidden by the popover for the 5th upsell.)

There are even more upsells below the fold.

There are even more upsells below the fold.

Of course nobody at Zoom decided 6 was the right number. While there is probably somebody at Zoom thinking about the 2-person startup UX, there are clearly 20x as many people concerned about increasing the number of customers who sign up for 500-person meetings. This dashboard is a veritable <marquee> banner that says “Our KPI is selling Large Meeting add-ons.”

Which I’m sure is logical! At least in the short term.

At the same time though, this stuff gives users the ick. “Avoid the ick” is not an OKR, and “% of users that hate navigating your settings” does not appear on your KPI dashboard. But it still accumulates.

When this kind of rot happens, it’s obviously bad. Any user can see it’s bad. But, importantly, enterprise customers don’t demand fewer settings, nor sane marketing position toward startups. So, often, these situations degrade.

It’s a tale as old as time. Occasionally a market leader who’s gotten off track will rally – especially if they’re still founder-led – to save themselves from fossilization and reinvent. In theory, Zoom could lever their position, in the center of billions of work meetings, into becoming a critical part of future AI-accelerated work.

More often, the gaps grow large enough that they spawn new startups. Blind spots and product debt compound until they recreate the situation that inspired Yuan in 2011: the market leader’s UX will be bad enough, and the potential for what could be will be compelling enough, that a worthy successor will launch. People will love it, and it will grow like wild.

Either way, we’ll look back on today as the bad old days, and appreciate how much better software has gotten. Customers will continue to demand better, and eventually someone will provide.

It’s the circle of life.