At Steam Clock we go to a lot of effort to make sure we ship apps with a high level of polish. Making your app solve the user’s problems well is the first 90% of building a great app. Polishing the hell out of that experience so it’s a joy to use is the final 90% of the work.

At Steam Clock we go to a lot of effort to make sure we ship apps with a high level of polish. Making your app solve the user’s problems well is the first 90% of building a great app. Polishing the hell out of that experience so it’s a joy to use is the final 90% of the work.

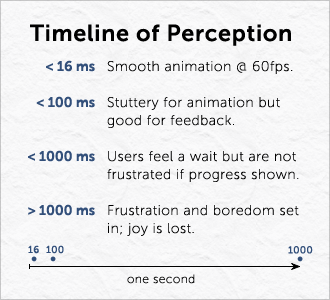

A huge component of that polish is responsiveness: giving the user an instant reaction to everything they do. Making your app faster and more efficient is good, but there’s more to responsiveness than speed.

60 frames

Your goal is 60 frames per second: the natural frame rate of the device, faster than the user can perceive. During animations and transitions, 60fps means a smooth transition with no stuttering. Although this is important for all animations, it is crucial in animations that are responding to a user’s touch. Even a very subtle delay between touch and response will give the feeling that the app is sluggish. This is a big reason that JavaScript “fake scrolling” gets such a negative response from users.

When responding to user feedback, 60fps means no stalling. If your app stalls for a frame on any supported device, it’s a bug. As long as the delay is small it might not be a high priority bug, but it is still an opportunity. Profile your app to get an idea of where your frame rate drops. It’s often worth keeping an older device to do this testing on, since if you can even get the older device up to 30fps, you’ll be in good shape on newer devices.

Actually getting a faster frame rate often involves either avoiding waste like drawing offscreen views, unnecessary opacity, or inefficient algorithms. Often though, getting a smooth frame rate involves moving work off of the main UI thread.

Threading

By default, any code you write runs on the main UI thread. If you do anything on the main thread that takes more than 16 milliseconds, you’ve dropped a frame and there will be a perceptible stutter. 16 milliseconds is a really long time, especially on newer hardware, so this isn’t as dire as it sounds.

Your biggest thread-blocking monsters are I/O operations. If you read or write a file or do any network operation, you need to do it in a background thread. On iOS this is a lot simpler than it is in plain C. The NSURLConnection class works asynchronously by default, plus Grand Central Dispatch and Blocks make most things straightforward to make asynchronous.

Although moving file, network, and data crunching to separate threads is important for any app, it’s doubly vital on mobile. Your phone doesn’t have a wait cursor, and its network quality can be incredibly bad. If you block for long enough, the OS will kill your app.

Spinning

Spinning

Now that your work is asynchronous, you need to let the user know something is happening. Provide a progress indicator if possible and worthwhile. Otherwise, get spinning.

Activity indicators (whether spinning, pulsing, or jiving) let your user know that you’re on the job and should go up after any perceptible delay. Without feedback, your app could have crashed, or it could have finished but without the results the user expected. You never want people wondering what your app is doing.

A special kind of activity indicator is placeholder content. Users can sometimes navigate through your app faster than you can render content, especially if you need to fetch something from the internet. For things like avatars and other peripheral information, a tasteful placeholder is definitely preferable to a distracting spinner.

Backend responses

So you have spinners now, but want to show them as briefly as possible. Although ideally you respond within 16ms, users are used to waiting for internet content to be delivered, especially when they know their wireless connection is weak. Even on a good wifi connection, your app’s request will have perceptible latency to get to the server and come back with a simple response.

Unfortunately, any time your backend servers take in responding is in addition to that latency. Every moment it takes for you to get a response back to the user is more frustration and impatience. Your goal should be to get content back to the user in 100ms1. After one second, users lose their feeling of task flow. On the web, users are intolerant of waiting for servers to respond. Within a mobile app, they are even less tolerant - if you can’t provide a faster experience than a normal web site, you might as well just have a web site.

Launch time

While launching an entire app in one frame is not likely, launching before the user feels a wait is possible, and launching in a second is often straightforward. Launch time affects the most important use case for your app: first use. If you can’t get the app loaded and fully functional in a second, you should at least get it awake and giving activity indication in that time.

Doing some simple profiling of app launch will usually reveal unnecessary work you’re doing at launch. Whether it’s building views that aren’t being displayed yet, loading content that isn’t necessary, or blocking on some operation that could be threaded, you can often get some easy wins without a lot of work.

Tap highlights

Every tap should have consequences when you lift your finger. First, though, comes an indication of a successful tap when you touch down. This provides a visual response for actions that cause a few frames to drop but last less than 100ms. Unlike with a keyboard or mouse, the user has no tactile feedback that they tapped successfully. They have no way of knowing they tapped on the right thing until it highlights.

Result: Joy

Congratulations! You now have a responsive app that is a joy to use. Of course, it also needs to be functional, usable, beautiful, and useful. But that is for another day.

-

IBM did this research decades ago, but Jakob Nielsen has various explorations of it online. ↩